The Cloud Forests

of Guatemala

Where the Forest Drinks the Clouds

in the Mayan Highlands

Scroll below the text for a gallery of Guatemalan Cloud Forest photos.

Professional Cloud catchers. Cloud forests exist in many places in the world, and they can vary dramatically in rainfall. But all Cloud Forests share one thing in common - their trees are skilled at catching clouds. When clouds are snagged, their moisture condenses on the vegetation and drips life-giving water to the forest floor. Tropical Cloud Forests, like the ones in the Guatemalan highlands, occupy mountainous regions relatively close to the ocean in relatively narrow bands of elevation - wherever the climatic conditions are just right for trees to apprehend passing blankets of clouds. When observing this phenomenon firsthand, as the clouds approach a forested mountainside the trees actually appear to breathe the clouds into the folds of their canopies. The mist that envelopes Cloud Forests is so dense that sunlight and temperature is dramatically reduced, while the humidity level soars. Decomposition is slowed by the low temperatures, and peat builds up in the dark organic soils. Cloud Forest’s signature plants include mosses, liverworts, ferns, lichens, and, in the New World, bromeliads - carpeting every horizontal and vertical surface available. Another common and striking inhabitant is the tree fern, an ancient plant growing to impressive heights.

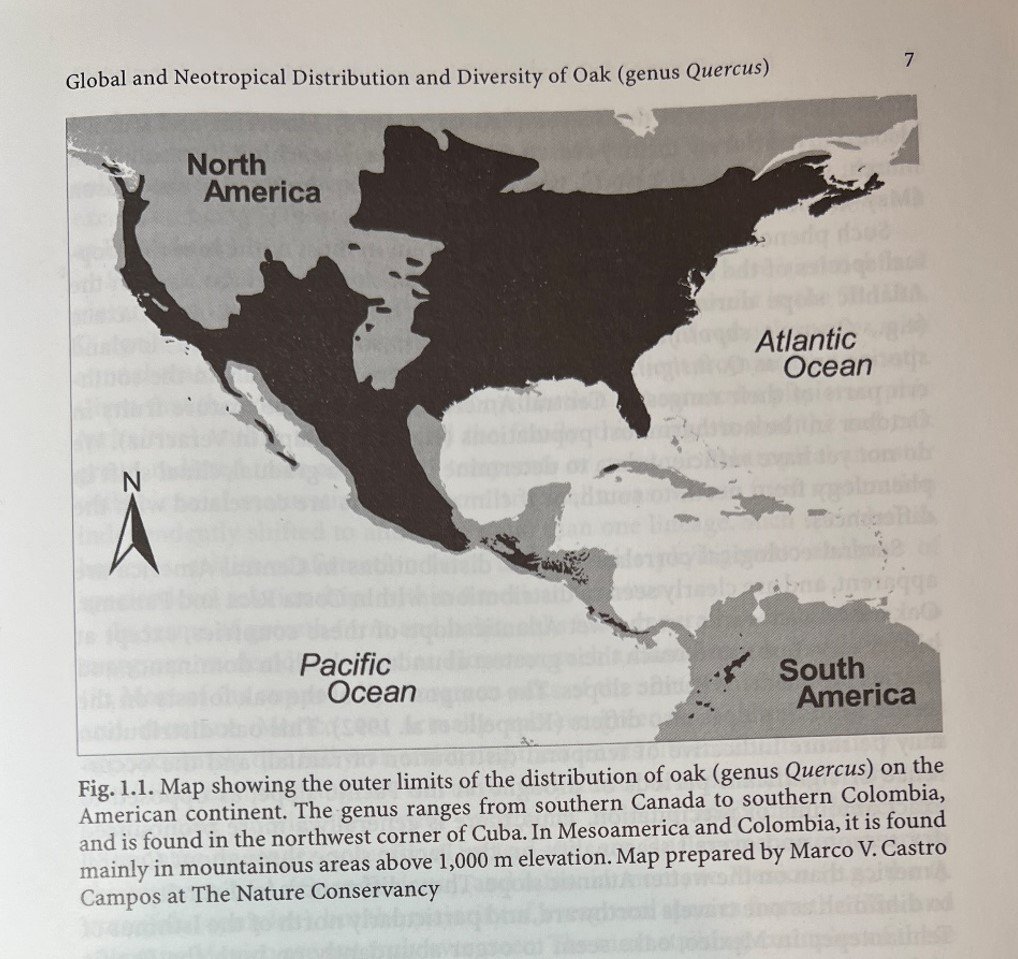

Guatemala Cloud Forests. Spectacular cloud forests exist on the ridgetops of Central America, including the mountaintops of Guatemala, all of which are associated with high rainfall. The “bones” of the complex forest community are the trees. And the primary trees are none other than tropical species of Quercus, some of them bearing the same common names of their Appalachian kin, such as white oak and black oak. Even their bark looks the same as their northern ancestors. This should come as no surprise, given that the lineage of these oaks arose in North America, It is believed the genus pressed southward into Central America during the glacially-cold Pleistocene era and adapted to a subtropical high-elevation climate. Today these oaks tower above their dripping understories, their branches and trunks covered with aerial vegetation. If ever there existed an “Avatar” forest right here on planet Earth, it would have to be these oak-dominated Cloud Forests of Central America.

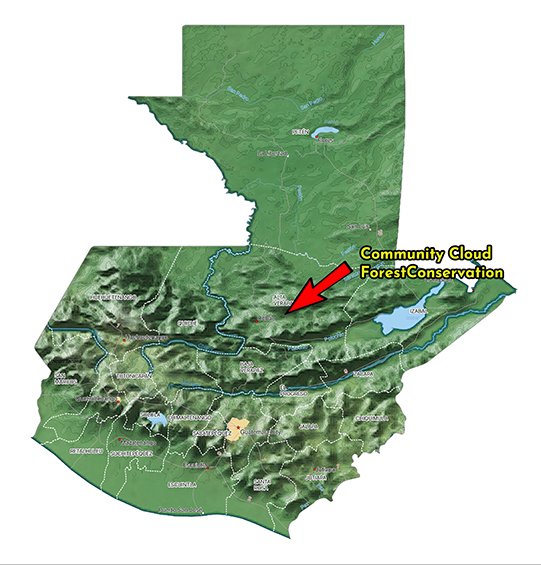

Catch-up Conservation. It is noteworthy that the forests of nearby Costa Rica and Belize are relatively well preserved. But due to Guatemala’s tragic history of instability, the country received little attention from conservation groups during the late decades of the 20th Century, when effective conservation was happening in so many other places across the world. Today Guatemala is trying to catch up, and some progress has been made in the Western Highlands and the Antiplano Highlands (also in the west). But most of the old-growth Cloud Forests in the Central Highlands, where Community Cloud Forest Conservation is located, are under the conservation radar and remain in peril.

The Appalachian Bird Connection. For those of us who love the Appalachian Forests of the Eastern United States, preserving Guatemala’s Cloud Forests is critically important because of the number of bird species we share in common. Ohio, for instance, sends 38 species of its breeding birds back to Guatemala each fall. Although Guatemala is not much larger than Ohio, it harbors a super-sized share of the population of many of our Eastern Forest’s neo-tropical birds.

Consider the wood thrush. The map shown below doesn’t just show the usual range map by country, but rather it shows the density of wood thrush populations in any one location by the intensity of the purple color. (Click here to see this map’s source - the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, NABCI) It’s hard to comprehend that all of the Wood Thrush scattered across the vast eastern third of our nation manage to compress their population into this relatively small geographic area highlighted in purple. Look for the purple band bank running east and west across the center of Guatamala. That’s the swath of mountains composing the Mayan Highlands, where tens of thousands of Wood Thrush spend autumn-spring every year, and where Community Cloud Forest Conservation is located.

Imagine if the forests highlighted in purple on the map above were to vanish, turned into agriculture fields for the production broccoli, cardamom, and avocados (a common fate in Guatemala). Such an ecological disaster would silence the Eastern Forests’ twilight gloamings. If we are to preserve the wood thrush and many of our other beloved Eastern U.S. birds, land preservation has to happen vigorously on BOTH ends of the avian arcs of migration, especially in those corners of the world that harbor high densities of birds. The migrating birds of the Americas are demanding that human stewards grasp the lesson that “we are all connected” soon - land to land, forest to forest, person to person. Very soon, because time is running out.

Endemic Birds. The nonprofit Community Cloud Forest Conservation works in the Central Mayan Highlands of Guatemala (see red arrow in the Guatemala map above). It may help you to visualize the geography if you realize that there are no Eastern Highlands, just Western and Central Highlands. The Western and Central Highlands belong to an internationally recognized center of high biodiversity and endemism that also includes the highlands of Mexico’s Chiapas, Honduras, and northern Nicaragua. This high-elevation region shelters gorgeous endemic birds such as the resplendent quetzal (the northern type of the species), blue-throated motmots, pink-headed warblers, bushy-crested and black-throated jays, and bearded screech owls. Alongside these world rarities, a wintertime bird watcher in this region could spy foraging black-and-white warblers, Louisiana waterthrush, wood thrush, hooded warblers, and Kentucky warblers - all signature birds of the Appalachian Forest’s heartland. It’s a humbling experience to see these birds in juxtaposition with Guatemala’s year-round residents, and it is heart-wrenching to see the vulnerability and scarcity of the habitat that supports so many of our migrating birds eight months out of twelve. If you think, “That’s not sustainable,” you would be right.

Trees in the Cloud Forest grow to immense proportions. Arc Staffer Andrea Jaeger

Towering Oaks take advantage of every square inch of available sunlight in this often sun-starved community

the giant leaves of Gunnera - an ancient plant with Gondwanan lineage, originated in South America NINETY MILLION years ago

Some of the Cloud Forest's mosses are nearly transparent

A cleared mountain side in the transition zone between oak-pine and Cloud Forest is being prepared for a new avocado orchard

Wood shelf fungus growing on a fallen forest elder

Every bit of vegetation, from mosses to the tree leaves of the giant oaks, drip with condensed moisture from the clouds

Clouds bank up against the Central Highlands

Late morning and the clouds begin building up in a high elevation Cloud Forest

Distribution of Quercus (oaks) in the Americas. Notice the band of oaks running across the breadth of the Guatemalan Highlands

Otherworldly Tree Ferns, representing over a dozen species, are ubiquitous in the Highlands of Guatemala

poetic moments abound when walking through a Cloud Forest when the sun can shine through the clouds at any moment

literally HUNDREDS of species of moss and ferns carpet the understories of Guatemala's Cloud Forests

Wood Thrush are very common sights in Guatemala's Central Highlands, hopping along the ground like robins. Photo by Mary Parker Sonis

Mosses cover the boles of giant forest elders.

Bromeliads bedeck the branches and trunks of every tree, boasting mind-dazzling species diversity.

Arc Staffer, Andrea Jaeger, admires a giant bromeliad on the forest floor.

One of the highest-elevation crops grown in the Guatemalan Highlands is cardamom, which, thankfully, is a perennial plant, a fact that minimizes soil erosion

Signature form of a massive old oak tree in the Central Highlands of Guatemala